Photo © Nicolas Junod

Fountains

Before everyone had running water at home, people came to draw water from one of the many fountains in the village for drinking, cooking, washing, and water for the livestock.

These basins, carved in limestone blocks by stonemasons, represented a hard labor which required up to 12 months of work.

The fountain attendant was in charge of the maintenance of the fountains and the pipes which fed them. He was well known and respected because he was a little master of the water.

Subsequently, the craft evolved, and when the fountains became simply decorative, the title of fountain attendant changed to assume the responsibility and the safety of the exploitation of the infrastructures of production of drinking water necessary for the food of households, businesses, industries and other consumers.

I propose here the history of the transport and the installation of the biggest basin (fountain)of Lignières of the XVIIIth century, located at about ten meters in the east of the old town hall, located near the house of Auguste Simon.

The largest of the five basins used to feed many pieces of cattle returning from grazing, it dates from 1750 and represents a considerable mass whose volume is as large in the earth as above ground.

Impressive in size, remarkable by the technical mastery if one thinks that it was cut in 1750, as indicated by the cartridge on its southern flank.

It was built by Abram Simon from Cornaux, under the governorship of Jean Louis Chiffelle and Abram Junod, whose initials are enclosed in a heart that also includes the arms of the community.

In the “Rochoyer-dessus” forest, the students of the normal school of Neuchâtel found in 1988 a large excavation in the Portlandian, a layer of Malm (very compact, gray limestone, very poor in fossils, hard, without obvious stratification) in which quarries have been opened in several parts of the canton, with a depth of 1m80, the west side of which still bearing traces of quarry tools.

This gaping hole was gradually filled with humus, so it had to be cleared by hand and shovel; Mr. Tony Perret's class completed the work of the students from the Ecole Normale. The site discovered deserves to be mentioned as a goal for a Sunday walk.

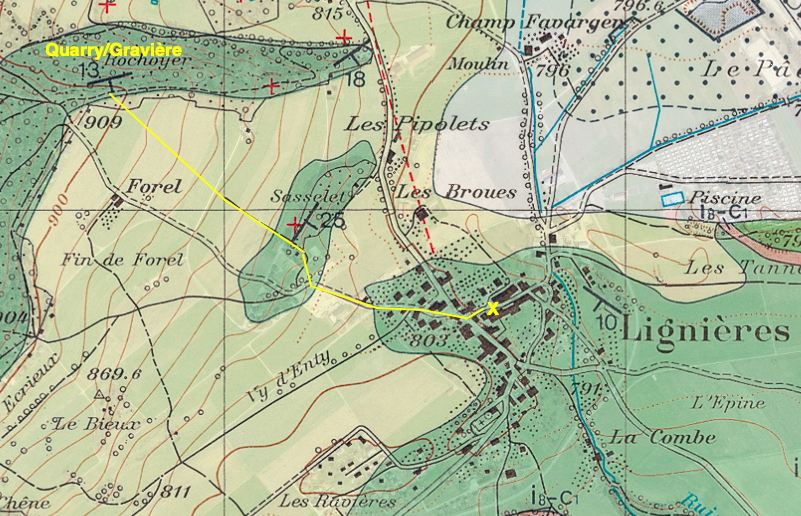

This place of extraction is one kilometer in straight line from the current location of the fountain (Fig 1).

Fig 1

Note

This translation of the original old French text (link) is far from perfect. I was not always able to find the English equivalent word which I left in “French”.

Let me know if you have any suggestion to improve the reading of this old text using the contact form on the left.

Story

The story of the transport of this basin was published in the “Musée neuchâtelois” of January-February 1903.

Wednesday, January 20, 1750 the community of Lignières, that is all “communiers” (members of the community), young men and all those who were on chores duty were for the first time in “Rochoyer-dessus” to demolish the cover - that the masons had made over the basin to work under cover - and the stones which the masons had raised were removed so that the so-called trough could be drawn (square stone or rounded by the angles excavated within or cut so that a thickness of not more than six inches is left around its circumference) as well as in the bottom to hold water) out of place and lift it.

We had already worked two days in a row, performing great chores squaring eight great trees of which four were of extreme length and large as co .... (the rest of the word does not exist in the story of the anonymous chronicler who did the narration). Also more wood to make humpback and accommodate several large rans of "fau" (beech logs) to make rolls. A quantity of wood prepared for the said trough such that there was almost enough to build a house.

On the 22nd of January, 1750, all those who were in a state to do the chores went to the “Rochoyer-dessus” to raise the said trough. For this purpose, three woods of length and thickness were used, such as large rafters and several small ones adapted as leversto which several ropes and chains had been attached to pull them down when they were erected using halberds, ladders and othersthings.

More than three jacks two that had been borrowed from Neuveville and one from Cressier, plus a large iron press (lever) and several “pressons”.

On the said day the said trough was raised about two and a half feet high. The basin was on all sides lower than the rock, except from Joran (North-West), where it was impossible to get it out, and it was necessary to break up and raise large blocks of stone at the end of it so that it could be pulled and lifted by the said end.

On the 23rd, half of the village with the masons raised the said trough about five feet high, and the four largest woods were put under it to pull it out along the said woods.

On the 24th, we made a floor with wooden squares. Three or four of the said rollers were struck (iron bound) in one end with holes to be able to turn them with iron presses in order to pull it out more easily.

And with the so-called vans to push last, presses, and turning the said rollers and about twenty pair of oxen in front, andother machines it was pushed over the sledge which was on the rock and it was cleared said rollers from below the trough that stayed on the sled.

This sleigh was made with two large "fau" woods (hearth) of over two and a half feet (75 cms) slaughtered (in diameter) that stood together by several spurs (sleepers) that crossed from one wood to another. And before putting the said basin on the sled, they put on said two woods, two antlered fir woods that were nailed with eight iron pins and this in order to lift the trough so as it he does not break the swords of the sled.

On Monday, January 26th, we put in front of the said sled, where we tied about forty pairs of oxen, and pushing last with the "voingues", "palanches" and "pauferre", it went so quickly because we put the sledge on several wheels and planks, that in descending rocks, until well before, it overthrew said tanks, dragged oxen and even people, that if it had not stopped it would have crushed people and animals.

This was a warning that served to take every precaution imaginable afterwards.

We have still brought all the oxen of the village and when we went to the field bar, we tied - to go down the "chézseau" - a fir tree with the branches and put the big rope of the pulley of the garret of the communal house of the village at the last corner of the said sled, where one tied a dozen pair of oxen to prevent it from slipping while crossing. And at the place of a "pierroyer" (pile of stones) which is in the field in front of the “Rochoyer”, passing underneath, we had a hard time because there was a lot of snow, forcing us to stop twice and, with much difficulty, looking up with the “aigres” and other machines, arrived and stopped at the end of the border of “Sasselet” to a field of the late Michel Bonjour. Because it was late, we left it there.

On the 27th we went to get it with the oxen and we put and chained after the sledge three big fir with the branches. And after thawing the sled with the “aigres” and machines, the four rows of oxen were put back. We passed the confines down the slope crossing the forest path above “Sasselet” and more than fifty people threw themselves on the said trees to hold the sled.

But when we came to a niche (flange of the ground with slope and slope) which is in the field of the late Michel Jaquet, currently belonging to Jacques Gauchat and J. Pierre Jaquet, it got up first, then pushed so hard after going down that people believed that everything would be damaged. But at the “Tirage” (today called the Gouvernière” the oxen stopped twice and we had to saw the pickets of the "closel"(orchard) belonging to the widow of Jacques Chiffelle, because the earth was frozen and the road too narrow to pass.

And in the middle of the “closel” everything stopped; it lasted a long time because of the lack of space. Only two rows of oxen could be used, except to move the sled that had been hitched up with a rope that had to be cut in order not to stop everything. We came to the place of the house to Jean David Chiffelle, above the lodge of Jaques Chiffelle. We could not go any further that day.

On the 28th, because of the fatigue of the previous days, each being almost weary of such a work, the resolution was taken to leave it for some time.

But some good children, especially the boys, having taken courage, objected and did everything to get back into action and to "remoder" (start again) we made five "aigres", two rows of oxen and a third to help each other, hitched it up with a rope that pulled straight off over the attic of the Chiffelle. It was necessary to cut the rope when it was time. We chained two fir trees and came to the village communal house where we had to turn the sled down to the fountain.

Capacity of the basin: 3240 “Neuchâtel pots” (4'860 litres).

The account of the anonymous chronicle ends here and the last lines seem to contradict a rather pleasant tradition born of the antagonism between the top and the bottom of the village about the place occupied by the large basin.

When the sledge in question arrived in front of the communal house of the village, the inhabitants wanted to stop there to install the basin.

But those below drove and whipped the oxen so skillfully that the sledge, thanks to the slope, could not be stopped, and it came as it did to the place where they wished to have it.

But there was already a fountain, probably wood, which had been considered good to replace by a stone trough, as it was done in 1755 for that of "Montillier" (at the entrance of the village coming from the Landeron) still by the care of master Abram Dumont stone mason in Cornaux.

Here is now the quarter of an hour of “Rabelais”; the chronicler, initiated into the secret of the commune, gives us the details of the expenses. We notice that the chore, people and animals, were absolutely free.

What said basin cost included transportation:

- To the carpenter who made the sledge, 2 écus bons 2 batz 2 crutz;

- The commune granted the mason 21 batz;

- To the bricklayer Abram Dumont in Cornaux for the trough 90 écus bons;

- Gratuities to his workers 8 écus bons 2 batz;

- More to his wife 21 batz;

- To David Descombes who helped himself to transportation 1 écu bon 17 batz;

- More to the bricklayer another 80 écus bons;

- For the two “Voingues”borrowed from the Neuveville 3 écus bons 13 batz;

- To (Mr.) Basin of Cressier for his “Voingue »21 batz;

- Expenditure 7 écus 16 batz;

- To the marshal for having recaptured damaged chains and tools 5 écus bons 2 crutz;

Total : 201 écus bons 2 batz 2 crutz

Some gratuity and indemnities granted raised the total sum to 233 écus bons and 23 batz, which represents 841.83 francs of our (1936) currency.

This basin still exists and bears the coat of arms of the municipality with the date of 1750 and the letters AB.N (Junod) and JL CH F. (Jean Louis Chiffelle) and below ADM (Abram Dumont).